Mail Correspondence with Soldiers at War (“Feldpostbriefe”): The letters of German soldier Kurt Reuber and his “Madonna of Stalingrad,” winter 1942/43 (Published on 26/12/2025)

Among the most famous field post letters written by German soldiers are those sent by theologian and physician Kurt Reuber (born on 26/05/1906 in Kassel, died in Russian captivity in January 1944) to his family between December 1942 and January 1943 from the Stalingrad cauldron. Drafted into the Wehrmacht in October 1939, he took part in the Battle of Stalingrad as a military doctor from November 1942 onwards.

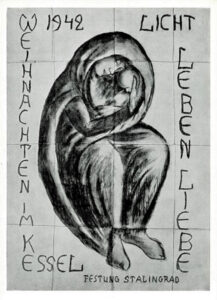

After the encirclement of the city in November 1942, trapping up to 300,000 German and Axis soldiers, Kurt Reuber drew a picture with charcoal on the back of a Russian map for Christmas 1942. It depicted a mother wrapped in a large cloak, holding a child in her arms, framed by the words “Licht, Leben, Liebe“ [“Light, Life, Love”] and “Weihnachten im Kessel 1942“ [“Christmas in the Cauldron 1942”]. With this drawing, which became known as the “Madonna of Stalingrad,” Reuber said he wanted to describe the great longing for light, life, and love in a situation of darkness, death, and hatred.

Kurt Reuber described his impressions of Stalingrad and his thoughts on the creation of the Madonna in various field post letters home, which are well worth reading and were published after the war.

He wrote (source: Bähr/Meyer/Orthbandt, Kriegsbriefe gefallener Studenten 1939 – 1945 [War Letters of fallen Students 1939 – 1945], p. 189 ff. [translation from German language]):

“Fortress Stalingrad, 3 December 1942

Difficult, difficult days of a situation previously unknown to me are now behind me. A dark Remembrance Sunday in 1942. Fear, dread, and terror, gloomy glimpses into a life with no return, with endless horror. Later on, we will have much to discuss; at present, the distance is still too short, matters are still too fluid, and the new situation is still developing.

You can hardly put yourself in our shoes, in our world of thoughts and feelings. You see the difficulties, you experience external and internal suffering, dark shadows all around, many become silent, others depressed, others change – not to mention the careless ones. Things fall into place, you see some clarity on the horizon. What floods of emotions and thoughts rise and fall. It’s not just about the big picture, but about your own life and your loved ones, who will have to go on living when it’s all over. You take a deep look into your own world and your surroundings. The real and the fake separate from each other.

The external situation: We are huddled together in a few holes dug in the ground in a steppe gorge. They are poorly dug and furnished. Dirt and clay. Something is made out of nothing. Hardly any wood to stockpile. Modest fire pits. Water fetched from far away, very scarce. Food still enough to fill us up. All around us, a dreary landscape of great monotony and melancholy. Winter weather with changing temperatures. Snow, storms, frost, sudden sleet. Clothing is good: padded trousers, fur vest, felt boots, and my priceless fur coat, my best possession in this situation. Haven’t taken off my clothes since vacation. Lice. Mice on my face at night. Sand trickles into the cave onto the camp. All around, the din of battle. We have good cover and are well entrenched. Saved-up leftovers are shared. One is involuntarily reminded of life in the trenches during the trench warfare of 1914 – 1918. Beams, mud cave walls, candles, huddled heads, silence, silence. Questions about the situation. »Serious« conversations, conversations about home, clinging to rumors, genuine humor, gallows humor, cynicism. The commander plays the harmonica into the silence: »Silent Night« (it was the first Sunday of Advent). Then memories of the beautiful life they once had flash before their eyes, with pleasure and temptation, love and shame. And everyone wants only one thing: to live, to stay alive! That is the naked, real, and true bottom line: the will to live, to live one’s own life. Serious conversations about God and the world. And outside, the terrible din of battle and destruction. – My heart is overflowing. I just want to share my present and recent past with you. Even in this situation, you should not be left in complete ignorance about me.

I am doing my duty. Caring for the wounded, especially transporting them away, is the most important task. And then I decided to give meaning to this misfortune. I bring the few destitute civilians who live with us in holes in the ground and the prisoners into the medical bunker and draw them. I have already produced some good work. I work so devotedly that I almost forget everything around me, hardly even hearing the noise of battle anymore. I am then almost happy.

Today I chose four-year-old Nina. She gave me her little hand and trustingly followed me into the bunker. I drew her sweet little face. Suddenly there was an air raid. I continued drawing because we were under cover. I calmed little Nina down. But then the bombs crashed down with a terrible roar. I took the little, whimpering Nina in my arms and threw myself to the ground with her. When the detonations were over, I continued working, albeit with trembling hands. But after a few seconds, I had to swap my pencil for the medical instruments.

In the evenings, since darkness fell at 2 p.m. – the long, long darkness – I read art history, and yesterday I studied physics and chemistry (electron theory) with my regimental doctor. – But how touched I was by your letters and those from the children, which I found on my return. I was only able to read them a few days ago. Oh, with what love and anticipation they are written. How far away is this good, beautiful world, and yet how close to my heart. I was very close to you and full of love and anticipation for the future. Right now! These monologues and dialogues with you now. How your words struck me: It could be the last letter I receive from you, that you receive from me. And what might this letter be like? I am so incredibly certain that we will see each other again. Never despair! If only I could relieve you of some of the burden of this long wait. It is harder for you than it is for us.

18 December 1942

It is the 28th day. We have not noticed the passage of time, but we have noticed its effect on us, how it is changing us. Everything is suffering, body and soul. I have had to tap into some mental and physical reserves. How often my heart has trembled, and how often melancholy has stood at the door or entered. Nevertheless, I must say again and again that I still have the strength to endure and resist. At times, I am overcome by a real joy in my heart. Patience, calm, and confidence have not left me for a moment, despite everything.

There is now a piano in the large bunker, which another unit had been transporting on a truck. Now our commander, the musician, plays the piano underground. Strange and unprecedented, this acoustics between the clay walls. How you hear music here underground! Suites by Bach and Handel, movements from Mozart’s Piano Concerto in A major, from Beethoven’s Pathetique Sonata, by Chopin and Schumann. And how well the commander plays. One is completely captivated by this music. One will never forget such musical hours! Captain Str. has just jumped in from the middle of the battle. He reports on the sad and painful experiences of his combat group. The conversation goes up and down like a wave. The commander plays again, while the walls reverberate with gunfire and bombings, and sand falls on us. We flinch and listen for a while, then the music takes over again.

Such a vast expanse now separates us – and yet I am so close to you. The sun shines over the wide, white steppe; soon it will set, but »it sounds as it always has«. Last night it suddenly dawned on me that I owe this strength that sustains me to being with you, with all of you. So I live here through you. –

Holy Night 1942

I don’t want to let this night pass without writing you at least a few words. But I am no longer capable of doing even that. It is almost midnight, and I am so exhausted and worn out from previous work and insomnia, from everything, everything, from the interplay of these days and hours, that I am really about to collapse. And my heart is so full – you know what with, and I don’t know where to put it. It must stay with me, another night, and tomorrow is another day. Then I will talk to you. Now it only speaks within me, so heartrendingly, and I see images of you inside me – oh, these images – but how strong sleep is – good night.

Stalingrad, Christmas Day, 25 December 1942, evening

It may be due to the seriousness of our situation that this Christmas was organized with touching love and devotion. Whether your empathy is great enough to imagine our Christmas: you can hardly guess. Consider our situation – our circle – steppe far and wide. No trees, no bushes. There is nothing here beyond the bare necessities of life. A piece of bread or wood is worth more than gold. The bare necessities are rationed as a precaution. What joy I bring my sick comrades with half a piece of bread that I save when I am full. Wood is fetched from our cleared former bunkers at the risk of our lives. Yesterday, a prisoner working for us fell while doing this. Warmth bought with blood! Our good Nikolaj with his pockmarked face. – A miserable snowstorm for two days, so that today the commander froze his ears on the 800-meter walk to the church. As a precaution, small reserves had been set aside for the celebration for weeks. From very, very secret corners, wonders of the world were conjured up, things that were hardly believable. And how skillfully and with what touching love the men prepared them. Adversity teaches prayer and other things, not least genuine human comradely love.

Everyone tried to make the others happy. How the men had decorated their bunkers! Advent wreaths made of steppe grass or »Christmas trees« made of wood shavings were everywhere. I went through all the bunkers, brought the men my drawings, and chatted with them. How they sat there! Like in Mother’s parlor at a holiday celebration. Harmonica, violin, singing, cheerfulness that one helped the other achieve, cheerfulness for hours in the glow of a few candle stubs. But it was dark in the corners of the bunkers, and in each one the sadness of the individuals was hidden, but every now and then it crept out. You can’t talk or write about that… At 2 p.m. there was a roll call in a balka, two songs, »Silent Night« and »Es ist ein Ros’ entsprungen… « How this bumpy male singing echoed across the steppe – you can’t talk about that either. And what was going on inside us… some eyes became moist. A short, sober speech by our commander, not without warmth, not religious, he probably didn’t want that either. Then bunker celebrations of camaraderie. The adjutant and I prepared our room and gift table, just like »at home«… Calling everyone in, handing out presents. Then, at the end, I joined my sick and medics for a celebration. The commander had donated a last bottle of sparkling wine to the sick. We raised our field cups and drank to what we love.

With our cups full, we threw ourselves to the ground, four bombs outside. I grab my doctor’s bag and run to the impact sites. One dead and three wounded. My beautiful festive bunker, bathed in Christmas lights, is transformed into a dressing station. I can no longer help the dying man. I can take good care of the wounded. They will survive. Two who were standing guard outside. The dead man, who had just left the party to go on duty, had said: But first I want to finish singing the song with you, »O du fröhliche…« A moment later, he was dead. Sad, difficult work in the party bunker. Our celebration was over. We still sat together. The mood was gone, and the desperate attempts made by one for the sake of the other were of no help. Actually, we were inwardly prepared for attacks on Christmas Eve. And so there were two artillery barrages. How it boomed through the Holy Night!

This morning, field service. Pastor E…. held services from 7 a.m. until noon because the tent is small. The tent walls fluttered in the snowstorm. A simple altar, we stood in a semicircle around it. Men singing, old Christmas carols, a sermon, prayer, and blessing. The conviction, the situation, the effect on the men, even the hunger to feel something uplifting – it was real and serious. What possibilities, what a task, what openness.

I must close. I am still well, especially on this unforgettable Christmas, into which I have completely »immersed« myself. You know how I thought of you. I had only one request: May my unspeakably beloved children and their mother find joy in all their sadness. It is night – but still Holy Night.

Fortress Stalingrad, after Christmas

The festival week has come to an end with so much going on, with thoughts, warlike events, with waiting and hoping, with calm patience and confidence. How the days were filled with the noise of weapons and a lot of medical work – and despite everything, also with my personal work in preparing genuine joy for my comrades! I worked on the following: four Russian landscapes. It was an artistic challenge for me, because I only had black chalk and found a brown pencil somewhere. People say I captured the steppe convincingly, especially the sky. Then I painted the six crew bunkers and the two officer bunkers for the general. I thought long and hard about what to paint – and the result was a »Madonna« or mother with child. Oh, if only I could create as my intuition dictates! My clay cave was transformed into a studio. This single room, no necessary distance from the picture possible! To do this, I had to climb onto my wooden bed or stool and look at the picture from above. Constantly bumping into things, falling down, pens disappearing into the cracks in the clay. No proper surface for the large Madonna drawing. Just a slanted, homemade table that you had to squeeze around, inadequate materials, a Russian map as paper.

But if only I could describe how deeply moved I was by this work on the Madonna, how completely absorbed I was in it, how everything seemed to me to be a blueprint for later works! The drawing is composed of large areas, shapes, and lines, everything simplified, remaining flat, like a fresco, but at the same time a sketch for a sculpture. This is also my approach here and there in the heads. I saw in the impressive effect that the essential content of the pictorial work and what it wants to express becomes transparent – almost unintentionally – through the objective, external artistic design. The image is as follows: child and mother’s head leaning toward each other, enclosed by a large cloth, security and enclosure of mother and child. The words of John came to me: Light, Life, Love. What else can I say? When you think about our situation, surrounded by darkness, death, and hatred – and our longing for light, life, and love, which is so infinitely great in each of us! At first, it is entirely physical, very different for each individual, and then it is transformed into a spiritual longing, this desperate longing for a higher world that remains faithful to the earth and yet rises above it. The words become a symbol of a longing for everything that is so little present externally and that in the end can only be born in our innermost being. I would like to hint at these three things in the earthly-eternal event of mother and child in their security. This earthly-concrete becomes transparent to me for the eternal backgrounds – and in the end it becomes Christmas, and then the Madonna appears before us.

I would like to say something else about the drawing: When I opened the Christmas door, the slatted door of our bunker, according to old custom, and my comrades entered, they stood spellbound, reverent, and moved, silently in front of the picture on the clay wall, under which a light burned on a log rammed into the clay wall. The entire celebration was influenced by the picture, and they thoughtfully read the words: Light, Life, Love. This morning, the regimental doctor came to me and thanked me for this Christmas joy. Late into the night, when the others were asleep, he and some of his comrades had to keep looking at the picture by candlelight from their beds, lost in thought. Whether commander or soldier, the Madonna was always an object of external and internal contemplation.

Fortress Stalingrad, 29 December 1942

You can’t imagine how happy I was when I found your airmail letter on my desk at 7 o’clock this morning. Finally, words from you again after weeks. We had almost given up waiting, resigned ourselves to the fact that the planes had more »essential« things to deliver day and night than mail, and that some things would be lost. Who could still complain about these circumstances in this situation?

How often have I been tormented by worries about you, by the thought of your anxious uncertainty, your darkest thoughts, devoid of all hope. And that there is no way to help you in your powerless waiting. The thought of this suffering, which is different from ours and in its own way even harder to bear than our inner and outer existence, is terribly tormenting. You poor, helpless women! – But now, for the first time, the connection between you and the outside world has been reestablished. Oh, and how it has been reestablished! I don’t know if I read your words with tears in my eyes, but if I did, they were tears of joy and gratitude that my hope that you would remain as brave and upright as you are in all your suffering, in all your unspeakable trials, in truly overcoming the world, and be a source of comfort and joy to the children, was not disappointed. You did it. You believed my words that, given the seriousness of the situation, I would not offer any consolation pills. I thank you for this victory. You took all the burden upon yourself and brought a bright sparkle back to the children’s eyes. So the light of Christmas still shone brightly and quietly upon them – I want to believe it – even if it was a quiet glow, like the sun on the evening of a rainy day behind the clouds. I know everything, everything.

Your beloved words from Job, »being lifted out of the jaws of fear into open space, where there is no more distress«, now have a vivid, literal meaning in their longing… How we await this hour, which He determines. What depths you must have traversed! Your words hint at it. And what heights you have nevertheless reached – I can also guess at those. Let it remain a premonition and a hint for now. Perhaps we will find the liberating word later. My heart and head are still too full and still completely caught up in the present. And it’s not all over yet…

Yesterday evening, I read Hans Grimm’s novellas, in which he writes so insightfully about frightened animals, about those that are hunted, herded into a cauldron… Can you imagine animals hunted by death, running for their lives, driven wildly around and then facing a life-and-death struggle – and then completely surrounded? What lies behind us – those first days when no one knew what to do, attack after attack from all sides, grenades, tanks, machine guns, the terrible Stalin organ [a Russian rocket launcher], bombs and all kinds of weapons, and everything face to face. But strength grows from resistance. You also get used to the situation. The crashing no longer startles you so much; you know how to behave in this situation. You have done what is necessary for your safety and calmly let the sand rain down on your head in your bunker and continue working or reading or talking… Around us, our own stable weapon stands guard, and how we trust it. The transport planes fly day and night. What does hunger mean? You can get by with little and even less. The situation of the sick and wounded is bearable again; I have medicine again.

As I crept through the snow tonight, a small Russian horse stood tied to our field kitchen, freezing and gnawing on wood out of hunger. I lingered for a moment with this poor creature. I am always moved by the misery of these poor animals. Today it served as our food. This eternal law of procreation and killing to preserve life, even in this vast, white steppe of desolation and silence. Tonight, the half-moon rose over it in a strangely moving way, as I had never seen before. And this starry sky, which one must look up at, regardless of the incessant, deafening roar of engines! These magnificent sunny days of mild, clear winter cold over the immeasurable expanse. How the splendor of these days captivates you and makes you forget what lies on the horizon all around. How kind the weather is to us these days, for our external fate and inner well-being. And even at half past four in the afternoon, you can still see the last glimmer of the day’s light shining through in the west. The days are already getting longer, for it was the solstice, and the green-yellow, light-hungry grass on my bunker walls is growing day by day. Life goes on.

New Year’s Eve in the Stalingrad Fortress

The old year is coming to an end. – Everything we have experienced has been immeasurably great! My letters, my drawings, our conversations during our only meeting this year – and how much has remained unsaid – have been an attempt at expression. I do not want to complain about the nameless suffering that has befallen me and my compassion for others – the winter campaign of 1942, the summer and autumn battles, and now our current situation and the many agonizing questions at the abyss of nothingness! I do not want to talk about that, nor about the small joys, the successes and progress. But if I may say something, something crucial, from the depths of my feelings and thoughts, then it is this: that I am infinitely grateful for everything with which this strange year has blessed me. Perhaps it has been the most significant year of my life so far in the light and darkness of our time on earth. I also know that it obliges me to do something significant.

I spoke of myself, but I should have said »we« instead, because where I go, you go too. You have suffered and experienced in and around my world, and you have done so in yours alone. How grateful I am to you for the words of Aeschylus from The Persians: »Give every misfortune its meaning and every day a drop of joy«. Wasn’t that the case with us? Shouldn’t it be so in the future and in the difficult, dark days of the turn of the year – days that are relentlessly dark in their own way for us, in their own way for you.

We don’t want to talk about the future; I can’t. And yet, I don’t know where I get the strength to live each day believing, hoping, and with a certain confidence.

Stalingrad, 4/5 January 1945, at night

I sit by the carbide light and begin a night portrait of myself in the hope that my commander might take it with him to Germany. Then a messenger interrupts me and says that the commander will probably be leaving tonight. Would the night portrait have turned out well? – Well, I want to continue working on it. It’s just a shame that the pictures I wanted to give you aren’t ready due to his sudden departure. In all this turmoil, everything is different from how it usually is.

6 January 1943

I wrote the previous note in a hurry because the commander was supposed to fly out. But suddenly the weather turned bad, so there was no departure. Waiting hourly on call. In this limbo, I managed to draw you a picture of myself. Perhaps you can see from it the circumstances under which it was created, partly during the day, partly at night, between medical work, the noise of battle, bombs, snowstorms, taking cover, and all the confusion – and from my view of internal and external things. I wanted to continue working, when suddenly I was called away and had to stop. Junkers planes have arrived, and the commander is taking everything with him. W. writes today of a cauldron that is only open at the top. Yes, upwards, inner and outer salvation!

Stalingrad, 6 January 1945 [Last letter to the children]

Today I gave my sick commander, who is flying to you, a package to take with him. One of the pictures is of your father; it belongs to your mother. »Little Nina« is for you, my youngest daughter. It is the little girl I took in my arms on the floor of the cave when I drew her. She was trembling and whimpering when the bombs were falling. Afterwards, she let me sit her back down on the box and continue drawing. The »Fortress Madonna« belongs to all of you. Your mother can tell you how good it is when people have a fortress within themselves in difficult times, so that they remain steadfast.

7 January 1943

With hardly any earthly hope left, facing certain death or endless terror in captivity, somewhere in a place of utter mercilessness. We now know what has happened around us. Initial hopes for a quick turnaround have been dashed; we know that we will have to endure for a long time to come. As far as humanly possible, I have so far managed to remain strong inside and not succumb to threatening thoughts of despair. We have dug ourselves deep into the earth that we love so infinitely. Everything else is enclosed in the eternal will of fate. You cannot imagine what this darkest of times means for a human life; these trials must have a blessing effect on us.

[Letter from captivity, delivered by a released prisoner after the end of the war]

Russia, Advent 1943

We don’t want to talk about how hard it is for us to be apart this year, and how much it hurts you the most. Even though I’m a prisoner of war, I know I’m still alive. But you’ve been told straight up that I’m missing. How the pain of your uncertainty gnaws at me, especially now during the Christmas season. Are you searching for me among the hundreds of thousands of dead in Stalingrad, or are you anxiously hoping that I am among the survivors? Are you telling yourself that your previous Christmas wait for me is now finally »in vain«? Oh, if only some message had reached you that I am still here, here for you!

Did you receive my last Christmas greeting from the Stalingrad fortress a year ago, which I gave to my commander when he flew out of the »fortress without a roof« shortly before the end? – A year ago – Christmas – Stalingrad. – How different our Christmas hopes were then! Your last letter told me so. Despite everything, you trusted in the promise of liberation. And us? We lived through and fought our way through the greatest Advent season of our lives in active anticipation of the arrival of our salvation – I would say, in a meaningful analogy to the mythical-political Advent expectations of those people at the turn of the millennium who waited anxiously for the arrival of liberation from internal and external shackles.

The mythical-political tradition surrounding Advent and Christmas became a grim reality for us. Few of us could have imagined, in an existence on the brink of nothingness, at the end, in the shadow of death, the fate of doom and destruction. We have been bitterly disappointed in our outward hopes for Advent and Christmas, because they were based on unreality. In the chain of guilt and fate, our eyes have been opened wide to guilt. You know, perhaps at the end of our current difficult journey, we will once again be grateful that through the apparent disappointment of our »Advent expectations«, through all the suffering of last year’s and this year’s Christmas, true redemption and liberation will be granted to individuals and the people.

When my Christmas greeting from last year reached you from the cauldron, you found a drawing for our command post, where we experienced the most moving Christmas celebration in the face of death – that mother, dressed in dark mourning clothes, sheltering her child bathed in light. Around the edge, I wrote the symbolic words of ancient mysticism: Light – Love – Life. Look at the child as the firstborn of a new humanity, born in pain, outshining all darkness and sadness. May it be a symbol of a victorious, hopeful future, which we want to love all the more ardently and genuinely after all our experiences of death, a life that is only worth living if it is radiantly pure and warm with love. In this way, we fulfill the deep meaning of our old Christmas carol:

The eternal light enters there,

giving the world a new glow.

It shines brightly in the middle of the night,

making us children of light.

I don’t want to talk now about the really big Christmas wishes that move the world: an end to war, a just peace, greater justice among classes and peoples. I am thinking of the words of the painter Franz Marc, who fell in the last war, which you wrote to me from his field letters in the cauldron: »Each of us has a great longing for peace. But what do most people imagine peace to be? A return to a life that is contrary to peace!« A bitter truth, then as now! How many are there who, even though the current horrific war is not yet over, insist in their minds that armed conflict is the only means of asserting themselves? The first prerequisite for true peace in the world lies in eliminating what is contrary to peace in our most personal lives. If we are honest, in this trying time of war, which is a time of critical self-reflection and longing for the great Christmas of peace, the solstice of all horrors, it has become clearer than ever to each of us what we must first eliminate everything which is unpeaceful and divisive in our immediate circle. For us prisoners, whose circumstances force us to reflect, the voice of conscience often speaks. Will we all follow it in the future, or will we return home unchanged? In the latter case, a dying comrade told me, we would no longer be worthy of the profound experiences of the rest of our lives. Without saying much about it, you can guess, my dearest wife, what this means for me, for both of us, and for our children.

I don’t want to lose sight of the depth of everything human, but also of what arises from it. – These images! The time will come when I will have to close my eyes, long and silently, in order to come to terms with these images within me. But in everything, I know of the ultimate soothing power. Like a great sculpture, the words of the psalm stand before me, now becoming more meaningful to me than I ever imagined: »If I make my bed in hell, behold, You are there.« In a solemn hour of reflection, I said them to my comrades, along with those other words: »Nevertheless, I will always remain with You.«”

In January 1943, Kurt Reuber was taken prisoner by the Russians and died in the spring of 1944 in the Yelabuga prisoner-of-war camp.

In August 1983, Kurt Reuber’s family donated the original “Madonna of Stalingrad” to the Kaiser Wilhelm Memorial Church in Berlin, where it remains to this day. Reproductions of the drawing are displayed in numerous churches in Germany, Austria, England, and Russia as a reminder against war.

(Head picture: Snow-covered landscape near Garmisch-Partenkirchen/Germany,

February 2013)

If you wish to support my work, you can do so here. Many thanks!