Thoughts on war: Viktor Levengarts on his father Lev Mikhailovich Levengarts, who died as a Russian soldier in 1942 (Published on 30/05/2025)

The old publications of the Deutsche Kriegsgräberfürsorge e.V. are – in the truest sense of the word – wonderful. Anyone who wants to find out more about people during and after the war, about their experiences, thoughts and feelings, will find in them a source written in sensitive words and striving for balance, which always places people at the center and reminds of what war means to them.

The book „Krieg ist nicht an einem Tag vorbei! – Erlebnisberichte von Mitgliedern, Freunden und Förderern des Volksbundes Deutsche Kriegsgräberfürsorge e.V. über das Kriegsende 1945“ [“War is not over in one day! – Reports from members, friends and supporters of Volksbund Deutsche Kriegsgräberfürsorge e.V. about the end of the war in 1945”] from 2005, in which war, imprisonment, flight and expulsion are described in all their facets by those who were themselves affected on different sides – as men, women and children. The reports are an emphatic reminder that war only knows losers among those who are exposed to it. At a time when, despite all the warnings of history, Western Europe is once again massively rearming and drumming up support for war, this cannot be emphasized often enough.

The book also contains a very readable chapter about the experiences of Viktor Levengarts and his family – his father Lev Mikhailovich died as a soldier in the Russian army on 28/02/1942 in the battle against the Wehrmacht – during the Second World War and his thoughts about people at war.

He writes (Volksbund, Krieg ist nicht an einem Tag vorbei! [2005], p. 232 ff. [translation from German language]):

“The photo is more than sixty years old. It stands behind glass in the bookcase, leaning against colored book covers. Two young people: He and she. Judging by the picture, he is very handsome, the face oval, the nose above the curved lips elongated and strikingly large. Curly hair frames the high forehead in small long waves. A calm gaze shining from under light eyebrows reveals something of deep joy. A dark suit, a white shirt, a tie. She leans her head against his shoulder. Her black eyebrows are as thick as if they were painted. Dark, soft hair covers her head like a small hat. Her large eyes reflect a feeling of perfect calm. These are my parents, a very beautiful couple. My mother is barely 28 years old in the picture, my father will be 31 in a month’s time. I didn’t exist yet. Years later came June 22, when the war began. After thirteen days, my father went to the front to join the People’s army. He had just celebrated his 36th birthday.

Certificate No. 282:

This is to certify that Lev Mikhailovich Levengarts is a soldier in the ranks of the army – Red Army soldier since July 5, 1941. Authenticated by signatures and stamps.

Pictures, letters, postcards and other little things in a house create the feeling that the people they are connected to are actually there. I hear their voices, see the expressions on their faces, their eyes. I talk to them. For some time now, this certification has been triggering the same feeling. It has long since ceased to be just a certificate, a piece of paper with words on it. Through it, my father is always present. When he goes to the front, I am three and a half years old. You could say that I don’t really know him, apart from a few fragments of pictures that have stuck in my memory from my tender childhood and will stay with us forever. Yes, I don’t really know him. However, my love for him has not diminished over the years. I can’t forget him, even if I almost can’t remember him.

He had gone to the front. His troop unit was near Leningrad, not far from the Luga. From there he wrote to my mother about how beautiful this river was. He believed that the war would soon be over and hoped to return there one day. He did not fight for long. His unit was surrounded and he was taken to hospital with fourteen shrapnel wounds. He spent a long time in a stupor. Then his condition seemed to improve, although he was still unable to use his arms. Finally, one of the biggest holidays came – November 7, the revolutionary holiday. Perhaps the hospital staff knew that my father had been a literature teacher before the war, so they gave him a volume of Lermontov’s complete works. This book is also in the bookcase. It is no longer just a collection of poems by my father’s favorite poet, but a piece of his life. A window into his time. It was the winter of 1941/42 when my mother received a message from the hospital:

Your husband, the Red Army soldier Lev Mikhailovich Levengarts, a native of the city of Yakutsk, was severely wounded in the fight for the socialist homeland and died on February 28, 1942, true to his military oath, proving his courage and heroism.

A little later spring began. If spring had come earlier, it seems to me today, father might have left more relieved. He died defending us. But he didn’t die in the war with the German people, with Germany, but in the war against a satanic machinery of evil.

I was recently on a business trip to Germany. Although 50 years have passed, I was afraid of feeling an inner bitterness, a hostility in this country where, as it seemed to me, the spirit of the past still hovers today. After all, I was traveling to a country from which the war came to us, and my father was one of its victims. The company I had been sent to was in Bocholt. I myself lived in Borken, a small town in north-west Germany on the border with Holland. In my limited free time, I strolled through the streets of this small town, visited stores and cafés, read the signs, watched passers-by, listened carefully to their conversations and tried to understand them. I smiled at them. They looked at me and smiled back.

Who are they? French, English, Italian? But no, they’re Germans, after all I’m in Germany. But how are they different from the French, English and Italians? They are probably hardly any different. One and the other are flowers growing in a meadow – camomiles, bluebells, cornflowers, violets. Their roots intertwine underground. They are part of a carpet woven by nature. If you plucked a camomile, the whole pattern would fade, lose its luster, remain incomplete. Something would be missing.

The books by Heine, Goethe, the Mann brothers and Böll stand side by side on the shelves of my home library, next to Pushkin, Lermontov, Block and Bunin, and the records by Glinka, Musorgsky and Tchaikovsky stand next to those by Bach, Beethoven and Schumann. In my album you can see the photos of Klaus Treptow and Manfred Claus. I studied with them at the university.

My father went to the front, not to conquer, but to defend. He was killed when I was four years old. Photos, certificates, notifications – in the past they were just a reminder for me, a kind of sign that should not be forgotten. Today, however, they enliven the house and create a connection between me and the people they remind me of. They have a priceless value.“

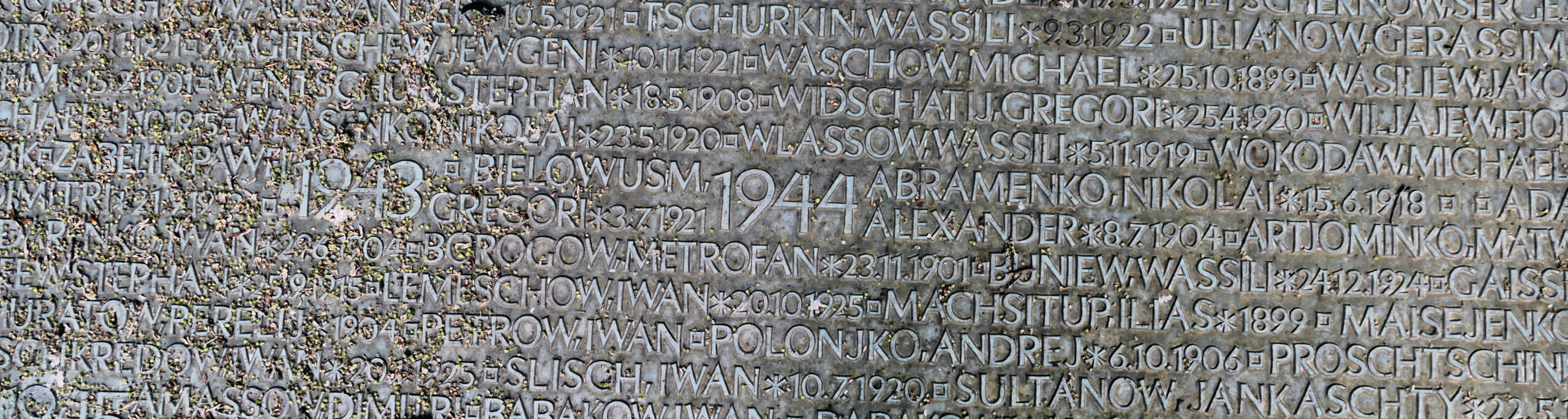

(Head picture: Memorial plaque for killed Russians

at the German military cemetery Bensheim-Auerbach, April 2022)

If you wish to support my work, you can do so here. Many thanks!